How I brought a Jewish wartime refugee’s lost fairytale back to life | Children and teenagers

This story begins in fever. It was the spring of 2021. and i contracted my first bout of covid. Bedridden, I turned to the pile of books that had been staring at me guiltily for weeks, if not months. The one I pulled was a soon to be released noir thriller called The passenger. Set in 1930s Germany, it follows a man on the run from Nazi authorities, hoping to escape by hopping on and off trains criss-crossing the country. As the Gestapo’s net tightens around him, he descends into paranoia and powerlessness. Maybe the coronavirus heightened the experience, but I was hooked. I tweeted that it was part Franz Kafka, part John Buchan and totally nail-biting.

But there was a twist. This was not a new book, but written almost a century earlier. The author was Ulrich Alexander Boschwitz, only 23 years old when his novel was published in 1938. and is a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany. In 1935 he crossed Europe to reach Britain, where he was promptly classified as an “enemy alien” and interned in a camp on the Isle of Man. He was held with more than a thousand other émigrés, including a remarkable number of artists, musicians, writers and intellectuals of what Simon Parkin called the island of extraordinary captives.

Eventually, the British authorities decided that some of these enemy aliens should be sent to Australia. After a hellish journey, Boschwitz was held in another detention camp, this time in New South Wales. Finally, in 1942, he was reclassified – now considered a “friendly alien” – and allowed to return to Britain. He boarded a ship, the MV Abosso, and set sail for what he hoped would be the start of a new life. He was 27.

But Abosso was spotted by a German submarine and torpedoed. The ship sank, killing 362 of those on board, the young, unfortunate Boschwitz among them. Lost with it was his revised manuscript of The passenger which, he was sure, would make an even better book.

But there was one more text he had left behind, a children’s story he had dreamed up while held on the Isle of Man. Long under 3000 words, it was called King Winter’s Birthday: A Tale. The original, handwritten manuscript, complete with drawings added by Ulrich’s mother, has lain undisturbed in an archive in New York for eight long decades.

I learned all this from Adam Freudenheim of Pushkin Press, the publisher who so successfully resurrected it The passengermaking it an overdue international bestseller. I had become something of an advocate for this novel, and now he had an unusual proposition to make. Would I take a look at Boschwitz’s forgotten tale and see if it could be presented to a modern audience? Could I, a political columnist and occasional thriller writer, relish the challenge of writing for children? The answers were yes and yes.

I read Freudenheim’s translation from the German, and my first instinct was that while I couldn’t exactly adapt the story, I could certainly draw inspiration from it. Indeed, the conceit at the heart of Boschwitz’s tale—Winter summons the other seasons, his brothers and sisters, to celebrate his birthday—suggested an idea to me the moment I read it.

Two seemingly contradictory solutions came to me just as quickly. First, I realized that this story would have to be aimed at children younger than those Boschwitz seems to have in mind. Older children might have accepted the idiom of a fairy tale – kings and palaces and the like – in the 1940s, but I suspected that their counterparts today would be far less patient.

after the promotion of the newsletter

At the same time, I had an enlivening thought about the story, which at first glance might seem an unlikely subject for the youngest readers. Yes, the structure of mine King Winter’s birthday is clear and the words are simple, but the plot turns to a seemingly demanding concept: the need to repair a world that has lost its natural balance.

Some may think this is too much for one child, but I remembered from my own experience as a parent and many decades ago in informal education that young children are often able to grasp the biggest ideas. Indeed, when it comes to philosophical questions that older minds wonder about – why are we here? What happens when we’re gone? How do I know this table is real? – there is a refreshing openness, perhaps brought about by a lack of embarrassment, among the very young.

Also, there is more of me in this short book than I expected. No spoilers, but this is a story about siblings and the pain that befalls those who can no longer be with a much-loved sibling who can only remember them instead. I am in this situation myself and I confess that I did not expect to find expression of this feeling in a debut title for children. It happened anyway.

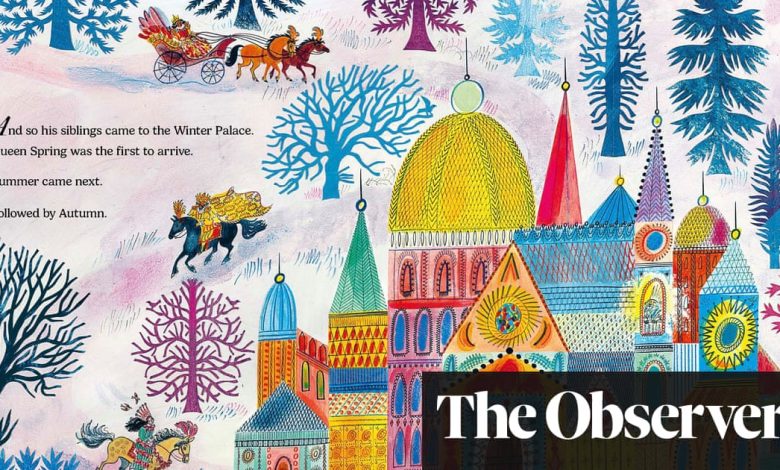

The result is a book that is more beautiful than I ever imagined it could be, thanks to Emily Sutton’s gorgeous illustrations. Between us I hope we have done justice to the imagination of this young man, a boy indeed who never stopped running—who was cut down in the spring of his life, and who never knew summer, autumn, or winter.

-

King Winter’s birthday by Jonathan Friedland and Emily Sutton is published by Pushkin (£12.99). In support of Guardian and Observer order your copy at guardianbookshop.com. Shipping charges may apply